A group decision that nobody wants | Just Reflections - Issue #43

Social pressures can make people say that they want and believe something that they really don’t want or believe.

Imagine a situation where we meet up with some friends and we have to jointly decide what we want to do together. The group may jointly assume that everyone wants to watch a movie when in fact no one does. So everyone in the group goes along with the idea of a movie to appear cooperative. We make a group decision that nobody wants. At the end of the event, we’re all dissatisfied after watching the movie when we all would have rather done something else. But when we leave, again wanting to be cooperative, we all say that we enjoyed it. Thus we create the impression that we enjoy watching movies together and set ourselves up for doing it again the next time we all meet because everyone thinks everyone else enjoys watching a movie.

I’m from Zimbabwe. One thing that really frustrates and confounds me is that there seem to be fewer Zimbabwean people who support Zanu PF than those who don’t. But every time elections come around Zanu PF wins, sometimes by wide margins. Sometimes this is attributed to rigging. Other times the argument is that I, and many others, am just in an echo chamber where I mostly hear the opinions of people like me and think that’s the majority when it’s not the reality. Other times, it’s that Zanu PF uses terror to bend the vote.

I don’t know what the answer is but—at the risk of simplifying a complex issue—let me offer what I believe to be another probable explanation.

In East Germany, before the Berlin wall came down in 1989, East Germans were almost unanimously in support of the prevailing regime. After the wall fell, very few people admitted to having been in support of the regime that had just fallen.

After several east European satellites of the Soviet Union fell in quick succession, The New York Times was full of stories about people who could finally speak the truth after years of not being able to criticize the regime. The paper was filled with stories from people who finally felt liberated. It then occurred to them after several weeks that they hadn’t covered the side of the communists. So they sent one of their reporters to Czechoslovakia to interview the communists and find out how they felt about the changes. In his first article from Prague, he said, “Everything has become so strange. A year ago, the Communists ran the country. Today, you can’t find a Communist anywhere.”

People who had made a career by rising in the communist party and running communist organisations were now all saying that they were not really communists at any post they were just playing along to feed their families and have a roof over their heads.

In the last issue, I spoke about how unchecked conformity can lead you to do things you disagree entirely with. We also saw that a person who hides his discontent about a fashion, policy, or political regime makes it harder for others to express discontent. Let’s think about this a little more.

When you choose a candidate to vote for on the ballots, are you really choosing the candidate you want? When you pick an outfit each morning, are you really reflecting your own sense of style? According to social scientist Timur Kuran in his 1995 book “Private Truths, Public Lies” there’s a good chance that you’re not. He attributes this to a phenomenon he calls “Preference Falsification”.

Preference Falsification is the act of misrepresenting publicly what we really think or believe or want privately because of the fear of the consequences or because we wish to gain some benefit. However, it also sometimes occurs in very innocent situations where there is nothing to fear. This is often where people believe the conveyed preference is more socially acceptable than their own. Falsified preferences might be described more simply, of course, as lies; but they are distinctly interesting kinds of lies, with particular social implications.

The penalties for voicing a private preference can be physical, economic, or social and can range from a negative remark, a disapproving gesture, or guarded criticism to unmitigated denigration, harassment, loss of reputation, imprisonment, torture or even death. People who are privately critical of an autocratic regime are quite likely to use preference falsification for their survival.

But autocratic governments are hardly the only cause of preference falsification. The perceived opinions of others very much determine what we say and do, even in the most democratic of democracies. Thus Kuran also points out that public pressure can impair liberty. And obstacles to free speech and honest interchange often come from our fellow citizens. So we need to be careful when we assess people’s choices and desires because they are not always given and fixed. They are a function of social conditions and all the pressures imposed by other people.

In some places in modern western society, it is risky to say that you are a devout Christian; in other places, you endanger your reputation if you say that you support Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter. Whatever you think about Vladimir Putin and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or regulating abortion, you will put your good name on the line among some prominent people if you insist on saying what you really think and it’s not aligned with popular opinion. The point is not limited to politics either. Whatever you think of the dinner and the conversation at your employer’s party, you are likely to say that you enjoyed the food and the company.

There are many socially significant consequences of preference falsification. Let’s look at two of them here.

The first one is the widespread public support for social options that would be rejected decisively in a vote taken by secret ballot. Thus, secret ballots ensure that preference falsification does not happen. They allow people to vote as their conscience or their interest dictates. Otherwise privately unpopular policies may be kept indefinitely as people reproduce conformist social pressures through preference falsification. However, others argue that secret ballots are good all the time because it is sometimes valuable to hold people’s opinions and beliefs up for public scrutiny. Make your own call here.

While secret ballots can mitigate against preference falsification in politics, secrecy in other spheres can encourage it. One of those spheres is the academic peer-review process.

“As every academic knows, anonymous referees, unleashing jealousies, animosities, and prejudices, are notoriously quick to condemn articles they would not dare to criticize openly,” — Timur Kuran

The second consequence is that in falsifying preferences, people hide the knowledge on which their true preferences rest. They distort, corrupt, and impoverish the knowledge in the public domain. They make it harder for others to become informed about the drawbacks of existing arrangements and the merits of their alternatives. Thus widespread ignorance about the advantages of change. Over long periods, preference falsification can dampen a society’s capacity to want change by bringing about intellectual narrowness and rigidity.

If certain thoughts are “unthinkable"—in the sense that people who entertain them are labelled uncivil or immoral—they may eventually become "unthought,” that is, they disappear altogether. Social pressures can make certain ideas disappear from public discussion. As this happens, people become less conscious of the disadvantages of what is publicly favoured and more conscious of the advantages. In the long run, private opinions will also move against ideas that are publicly disfavored. For example, if you have never heard that women should be educated equally with men you may not even think of it at all.

The first of these consequences is driven by people’s need for social approval, the second by their reliance on each other for information. For example, according to this 2020 study, the vast majority of young married men in Saudi Arabia express private beliefs that support women working outside the home, but they substantially underestimate the degree to which other similar men support it. Once they become informed about the widespread nature of the support, they increasingly help their wives get jobs.

Kuran offers a simple framework for explaining individual and collective choices based on three factors, which he describes as intrinsic utility, reputational utility and expressive utility:

“A person’s purely private preference is based on the intrinsic utility, to him, of the options under consideration. Some people really want to get rid of affirmative action or welfare programs, because they think that these are bad things, but their private preferences may not be expressed publicly, because of the loss of reputational utility that would come from expressing them. The importance of reputational utility in a particular case depends on the extent of the risk to your reputation, and also on how much you care about your reputation. And people get what Kuran calls expressive utility from bringing their public statements into alignment with their private judgments. We all know people who hate to bow before social pressures; such people are willing to risk their reputation because what they especially hate is to speak or act in a way that does not reflect their true beliefs. Kuran says that a person’s choice of a public preference depends on these three variables, and hence that people’s expressed views–their public preferences–are very much a product of what they think other people think.” — Timur Kuran

As people’s thoughts about other people’s thoughts change, there is a shift in reputational incentives, and hence people’s public preferences can shift: if you come to believe that there is a “silent majority” believing what you believe, you probably won’t be silent for very long. For social change to occur, expectations are crucial, very much because they affect people’s public preferences. And when people’s perceptions of what other people think are shifting rapidly, there can be a bandwagon effect.

Suppose that you believe that women and men are equal and should be afforded equal rights and opportunities. Suppose, also, that this belief is inconsistent with existing social pressures. Eventually, you may change your private belief, making it conform to those pressures and accept that everyone has their place in the social structure. This is because it can be extremely frustrating, even distressing, to believe something that other people think is implausible, offensive or stupid. In order to reduce cognitive dissonance, you may even bring your private preferences into line with perceived public opinion. In this way, people who are oppressed by the status quo can come to collaborate in their own oppression.

This is not a completely contrived example either. There are many recorded instances of oppressed groups showing acceptance of their deprivations as fair. Treating their wretched existence as natural, and being complicit in a system that degrades them.

Maybe this offers some answers to the Zanu PF situation. Maybe Zanu PF rule has persisted not only, or not mostly, because of brute terror but also because of a pervasive culture of falsification. People joining organizations they hate. Following orders they consider nonsensical, cheering people they despise and ostracizing opposition leaders they admire. Either that or people secretly think Zanu PF is the best option we have. Sure we complain together on social media and saying Zanu is bad is the popular thing to say. But when crunch time comes. When people are alone at the ballot, they express their genuine desires.

That’s all I have for you this week. If you like the newsletter, consider sharing it with others on Twitter, WhatsApp or Facebook. Hit the thumbs up or thumbs down below to let me know what you think.

I hope I’ve given you something to think about this week and I wish you ever-increasing curiosity.

Until next week.

BK

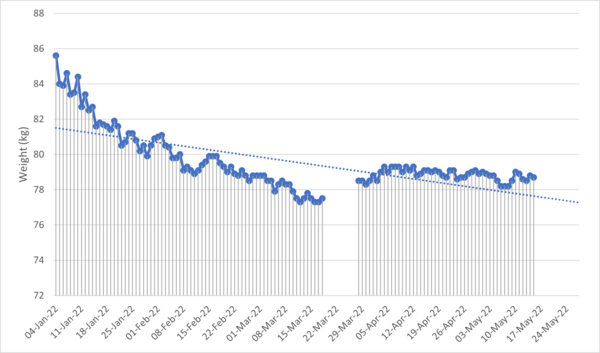

2022 Resolutions:

Weight: Get to 75kg by April 28 and 70kg by July

Had another good week in terms of exercise this week. I went cycling in the city on Sunday, went skating for several days during the week and capped things off with a nice long hike. That front’s getting better but I am still eating uncontrollably. I haven’t gotten back on track with that yet. Let’s see how this week goes.

Sleep: Consistently sleep avg. 8 hours per day

Averages this week:

Duration: 6h 59m.

Avg. bedtime: 03:33.

Avg. wake-up time: 10:32.

Another good week on this front. Yeah, 8 hours is pretty high, I feel pretty good with 7 hours. But I’ll keep trying.

Business: Start a business in 2022

Nothing much to report here. Working on feature requests and fixing bugs probably for the rest of the month.

Impactful ideas that challenged my thinking.

I have a lot of interests so I'm always learning all kinds of things, some of which really challenge my thinking. In the Just Reflections newsletter, I'll be sharing with you a summary of the ideas that challenged my thinking recently and hopefully they will challenge yours too and we grow together.

In order to unsubscribe, click here.

If you were forwarded this newsletter and you like it, you can subscribe here.

Powered by Revue